| Interiors of Virginia Houses |

|

From "Interiors of Virginia Houses of Colonial Times" by Edith Tunis Sale, William Byrd Press, Richmond, 1927 |

|

Rosegill The great plantations of the Rappahannock River are linked together by ties of affection and con-sanguinity, very interesting on the part of those involved in them in the acceptance of the relationship and of great value in any genealogical search in this locality. The Beverleys of Blandfleld, the Carters of Sabine Hall, the Robbs of Gaymont, the Garnetts of Elmwood, the Sales of Farmer's Hall, the Tayloes of Mount Airy, the Brooks of Brooke's Bank, the Wormeleys of Rosegill, with other families of distinction have married and intermarried until it would seem that one huge family tree would have a twig for each. In tying the name of family and estate, authentic genealogy is given in very few words. In writing the saga of Rosegill, there is but one family that comes to mind and that is Wormeley, whose country seat on the high bluff of the Rappahannock is strikingly individual. Certainly no Colonial manour-house was ever built at greater care or cost. This magnificent plantation came into being shortly after the settlement of Jamestown and can be traced back to the year Sixteen-forty nine, when Ralph Wormeley -- who, with his brother, Christopher, had emigrated to Virginia in Sixteen-thirty -- received a Crown grant of thirteen thousand acres. There seems to be no definite knowledge of the exact year the dwelling was erected, but it was undoubtedly begun by the patentee who soon after his arrival in the Colony became a number of the King's Council and of the House of Burgesses. The same year that Ralph Wormeley received his grant, Norwood, the traveller, speaks of Rosegill. His "Voyage to Virginia" states that he landed at the Ludlow plantation on York River where he was well entertained. "But," he continues, "It fell out at that time that Capt. Ralph Wormeley (of His Majesty's Council) had guests at his house (not a furlong distance from Mr. Ludlow's) feasting and carousing that were lately come from England, and most of them my intimate acquaintance. I took a sudden leave of Mr. Ludlow, thanking him for his good intentions towards me; and using the common freedom of the country, I thrust myself amongst Capt. Wormeley's guests in crossing the creek and had a kind reception from them all which answered (if not exceeded) my expectations." From this, one finds without doubt that there was a dwelling at Rosegill shortly after the settlement of Jamestown. [Wrong. Ludlow was describing visiting Ralph Wormeley at his house on Wormeley's Creek, York County. It was not until 1650 that the General Assembly allowed settlers to settle in the area around Rosegill because of a treaty with the indians.] |

Rosegill, showing manour-house between kitchen and present dairy. Founded by Ralph Womeley I, about 1649.

|

The handiwork of the builder of Ralph Wormeley's great house faithfully carries out the aggregate of the contemporary phase of domestic architecture in the country from whence he came. Until after the Revolution there was no line of any consequence drawn between builder and architect, and as the owner of Rosegill was, like William Byrd later, a cultivated amateur, his knowledge of construction, though superficial, united to an academic understanding of the necessary principles of architecture, enabled him to play a very important part in the house he built. Then, as now, Rosegill crowned a steep hill above the village of Urbanna, overlooking from the water front on the northern flow of the river, the opposite shore five miles away. On Halkuyt's map, the Rappahannock is called "Toppahannock or Queen's River." In a description of this very large house given many years ago one may read: "The house was built of red brick. It had a chapel, a picture gallery -- a noble library and thirty guest chambers. It stood overlooking the mouth of the river and a high wall at the water's edge protected the lawn." This sketch does not apply to the Rosegill of today, so must he treated more as tradition than history. At present, though it still remains a "superb building of early Virginia," the walls are part brick, part siding, and all are painted white. Nor does the lawn run direct to the water's edge, for a beautiful grain field waves between the two. Today one sees no building capable of entertaining a great number of guests, the third storey of the house being the only large space and this can accommodate fourteen beds. These, however, are but minor criticisms, for Rosegill is still a "greate house" just as the plantation, although smaller in acreage, is a splendid modern farm. Full eighty feet long and half as wide, with a height of three storeys protected by an unbroken gable roof, the three-part composition, consisting of the main dwelling, the kitchen and the dairy, although all stand independently of each other, presents a view of Colonial magnificence. In the erection of these three buildings to serve as one there is no loss of the correct sense of form as that sustained in the utilitarian era of the nineteenth, century. The distance between the dairy and kitchen from the dwelling is much greater than between the unattached wing and the main house at Carter's Grove, but the balance is perfect and the effect even better than if covered ways had tied the three together. The Master's House and the service buildings are double fronted, which is of great advantage to the lawn. The formal entrance front of Rosegill is on the river, for when the plantation was founded the gentry used altogether the water highways, each family possessing one or more galleys manned by negro oarsmen. The first storey is built of brick covered with a white cement wash, but the other two are of siding which may still have brick underneath. The gable roof appears to be of very low pitch owing to the extraordinary width of the central dwelling, and the most important exterior feature is the chimney line where, holding their caps high up towards the clouds, the four chimneys on the main house with two upon each of the lesser, gives from a distance between foliage broken lines, the effect of a tiny village. Forty windows, the majority of twelve-light proportion, cut into the walls on both fronts and the two set in the gable ends, having such a large space to make light, were given sixteen panes of glass. |

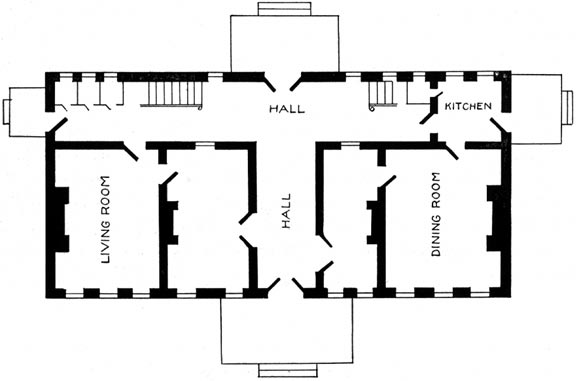

First floor plan of Rosegill.

|

|

Go back to Library